Kim Possible: Explaining North Korea's Suddenly Friendly Behavior

April 28, 2018 | What’s up with North Korea? Are they feeling okay over there? They were launching missiles just months ago into the Pacific Ocean, and now I get to see photos of North Korean “Supreme Leader” (read: dictator) Kim Jong Un and South Korean President Moon Jae In holding hands like an annoying couple that overshares on Instagram.

Because unbiased news from the Hermit Kingdom is hard to come by, it is difficult to know exactly what motivates North Korean leadership. Some think the escalated brinkmanship of 2016 and 2017 was unproductive for North Korea, so they switched strategies. This smells a little fishy to me. Why would North Korea promise destruction to its super evil arch nemesis, the United States, and consistently threaten states nearby, only to announce a desire for a peace with South Korea? I haven’t heard of a plot twist so extreme since the last M. Night Shyamalan movie came out.

Here’s what bothers me:

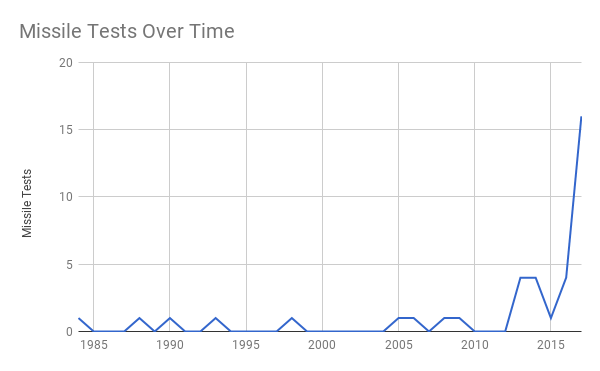

This is a handy-dandy chart of North Korean missile tests over time. Please note that this includes only missile tests or other tests meant to assist in missile delivery, not satellite launches or the deployment of conventional artillery.

The pointy part at the far right of this chart is what we in the field of international relations call a seriously, bigly large change in the dependent variable (DV). The DV in this case is missile tests, and the independent variable—the thing causing the tests, or what the DV depends on—is, well, kind of unknown at this point.

It is also important to note that the chart cuts off in 2017. There were 14 discrete tests in 2017—23 total missiles launched—and exactly zero have occurred in 2018. Why the extreme escalation and then sudden drive for peace? It’s creepy and I don’t like it.

My current pet hypotheses are three:

Hypothesis 1

I believe this to be the least likely scenario. North Korea is doing this to catch everyone off guard and is planning an attack on South Korea. I don’t have any concrete evidence for this, hence why I don’t think it’s likely. Additionally, that would end poorly for North Korea. South Korea has the strongest military power in the world as an ally, and the international community would react very negatively. That includes China, North Korea’s only true friend—frenemy?—for the time being.

Hypothesis 2

This is my personal favorite, mostly because I have a weakness for domestic level theories in international relations literature. North Korea has been impoverished for decades. Most of the population works in agriculture, and the economy is so strictly controlled by the state that it makes the Soviet Union look like a hippie mom who lets her kids play outside with no clothes on. While there is a sizeable population of “middle class” citizens and elites who live in the relatively developed capital, Pyongyang, most of population lives chronically malnourished, without access to the Internet or real education, and in consistently underdeveloped environs.

It’s hard to know exactly how stable or not day to day life is in North Korea. In this scenario, North Korea is seeking peace with South Korea because it is financially struggling to such a degree that North Korean leadership is worried about violent revolution. By seeking peace with South Korea, it is averting a potentially fatal ending for North Korean leadership. Violent revolutions and similarly radical political events have occurred throughout history, and it’s not out of the question for North Korea. This historical precedent and the economic realities of contemporary North Korea are what make me think this scenario is most realistic.

Hypothesis 3

While more believable than the first on the grounds of pure logic, this hypothesis also lacks evidence that is publicly available. It is somewhat compatible with the second hypothesis, but can stand on its own as well. In this scenario, the escalation of missile tests in 2016 and 2017 and sudden peacemaking in 2018 are not separate events to be contrasted with one another. North Korea could have been seeking peace with South Korea and other global powers from the beginning, but wanted to ensure that it had the upper hand in negotiations. By being more aggressive initially and then showing a sweeter side in a classic carrot-and-stick dichotomy, North Korea is in a better position than if it simply made moves to make peace immediately.

Lastly, there is a good chance that other motives and third parties not expanded on here have had significant influence on this new peace initiative. I personally think China has likely hand a much larger role in this, given its relationship with North Korea.

Unfortunately, the opacity of the North Korean government renders knowing what the actual truth is, at least for the time being. Assuming nuclear annihilation doesn’t await us at the end of this chapter of Korean history, I greet this new peace initiative with great caution. I would have previously said that peace on the Korean peninsula was impossible in my lifetime, and I hope I can continue to be wrong about this.

Sophia Freuden is a recent participant in the Fulbright Program and former intern for the U.S. Department of State.

The views expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect the views of other Arbitror contributors or of Arbitror itself.

Photo by Vietnam Mobiography with a CC BY 2.0 license.